In living rooms and courtyards across Pakistan, women are running businesses that keep families afloat. From tailoring to catering, handicrafts to home-based services, they are hardworking and resourceful. Yet despite their effort, most remain excluded from the formal economy. They lack bank accounts, access to credit and the digital tools that could help them grow beyond survival.

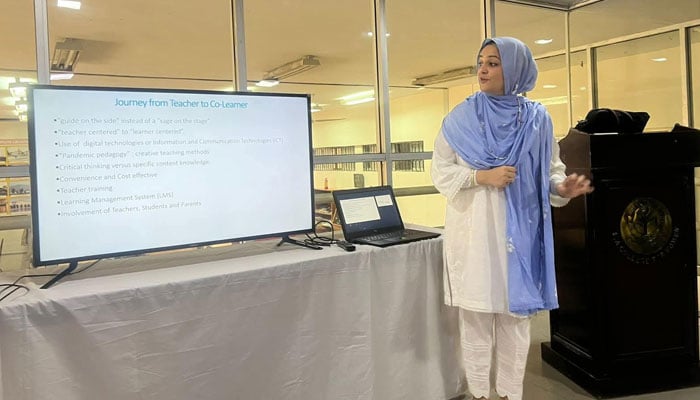

It was this reality that inspired Dr. Subeika Rizvi to focus her doctoral research in Pakistan on women’s financial literacy and entrepreneurship. In this conversation, she explains what drove her work, what she discovered, and why financial empowerment is central to Pakistan’s future.

Q. What inspired you to work on women’s financial literacy in Pakistan?

Dr Rizvi: My journey started with what I saw around me. Talented, hardworking women were running small businesses from their homes, but unable to grow beyond a certain point. They were resourceful in every sense but lacked access to financial tools, knowledge and networks.

When I began my doctoral research, Financial Literacy, Financial Inclusion and Women Entrepreneurs in Pakistan, I realised the problem was much deeper. Many women did not have a bank account in their own name, had never applied for a loan and felt excluded from the financial system. What inspired me most was their resilience. Even with limited resources, they created value for their families and communities. I wanted my research to be more than an academic exercise. I wanted it to provide a blueprint for change.

Q: Can you tell us a bit about your research and what makes it unique?

Dr Rizvi: Most studies look at either financial inclusion or entrepreneurship separately. My research connects the dots between financial literacy, access to finance and entrepreneurial growth. Using gender-disaggregated data, I found that only 13% of women in Pakistan have a formal bank account, just 1.5% have borrowed from financial institutions, and women entrepreneurs make up a mere 1.4% of adult women compared to 21% of men.

Another important aspect of my research is that I did not only measure financial performance. For women, success also means autonomy, decision-making power and confidence in business management. These non-financial indicators are just as critical.

Q: Why are so many women in Pakistan excluded from banking and digital finance?

Dr Rizvi: There is no single reason. It is a mix of cultural, institutional and practical barriers. Many women, especially in rural areas, have no nearby bank branch or agent. Documentation requirements discourage those working informally. Cultural norms often mean women need permission to travel to a bank or attend training. In many households, men are seen as the ones who handle financial matters.

Low financial and digital literacy also limits uptake. Even when women have mobile wallets like JazzCash or Easypaisa, they often rely on male relatives to operate them. Finally, financial products are not always designed with women in mind. Loan conditions, repayment cycles and digital platforms often fail to reflect the realities of women’s businesses.

Q: What are the main barriers women face when using mobile wallets or online banking?

Dr Rizvi: Digital literacy is a major one. Many women have smartphones but are afraid of making mistakes. Phones are often shared with male relatives, which undermines privacy and control. Trust is another barrier. Women worry about fraud and scams and have little access to customer support. And many products are not designed for women’s needs. For example, a woman running a microbusiness may need tools for small, frequent transactions, but those features are rarely highlighted or marketed to her.

Q: How do your training programmes help women feel confident with digital finance?

Dr Rizvi: My goal is not just to teach women how to use a tool but to make them feel ownership over it. We start with very practical, hands-on sessions. Women create accounts, send transfers, pay bills and check balances. This builds familiarity and reduces fear. We also cover security, showing them how to verify transactions and protect against fraud. And the training is tailored to their context. A woman selling on social media has different needs from a home-based tailor. We use hybrid models too, combining in-person workshops with WhatsApp support so women can revisit lessons anytime.

Q: Can you share a real example of a woman who benefited from your programme?

Dr Rizvi: Ayesha, a 32-year-old from Hyderabad, had a small tailoring business but relied only on cash. After attending the training, she began using JazzCash and Easypaisa, promoted her work on WhatsApp and Facebook Marketplace, and soon started receiving orders from major cities. Within three months her income doubled. She was able to buy a new sewing machine and enroll her daughter in a private school.

Another participant, Shaista, realised she could expand her client base by using mobile wallets for payments and social media for advertising. “After the training, I created accounts with JazzCash and EasyPaisa, which made payments much easier,” she explained. “I also began posting ads on university pages and new clients started finding me online.”

Q: How well is the ‘Banking on Equality’ policy working so far?

Dr Rizvi: The State Bank of Pakistan launched it in 2021 to mainstream gender equality in finance. Some progress has been made. Women now make up about 17% of the financial sector workforce, up from 13%, and the number of women with active bank accounts has grown. But the gender gap remains large. Forty-seven percent of adult women have an account compared to 81% of men. Policy alone is not enough. We need awareness on the demand side and better product design on the supply side.

Q: What more can banks, fintech companies and the government do?

Dr Rizvi: They can design microloans with flexible collateral requirements, introduce Shariah-compliant products in conservative areas, run digital literacy workshops in regional languages, and work with NGOs and women’s chambers to reach communities. They can also adopt train-the-trainer models, so women who gain skills can pass them on in their communities.

If you could change one thing tomorrow to help women join the financial system, what would it be?

I would simplify account opening. Mobile-first, low-documentation processes would allow millions of women to register easily.

Q: What is your hope for women’s financial empowerment in the next ten years?

Dr Rizvi: My hope is that financial empowerment will become the norm, not the exception. Women will run larger businesses, manage money confidently and contribute to Pakistan’s economy on equal footing with men. Financial literacy is not just about money. It is about dignity, autonomy and opportunity.

The stories Dr. Rizvi shares remind us that women in Pakistan are not waiting for opportunities. They are already creating them with whatever little they have. What they need is recognition, support and the right financial tools to grow. If policies, banks and communities can work together to remove the barriers, women’s financial empowerment will not only transform households but also strengthen the country’s economy.